Frances Wright

By Andrew Pouncey

Last week, I received an email from the great great granddaughter of Frances Wright. No kidding! She lives in New Jersey and was seeking additional information on Granny Fanny as Frances is known to the family.

I have been holding out on writing about Frances Wright because she is a well-documented resident of Germantown, and I knew when I really became desperate for good material, I could count on Frances.

This new connection pushed that timetable up. Of course, you won’t find Frances in the phone book. Frances first came here in 1825 and at one time owned both sides of the Wolf River, between present-day Kirby Parkway and Germantown Road, and south to the railroad.

Frances (Fanny) Wright was born in Dundee, Scotland on February 6, 1795. She was orphaned at three and sent to live with relatives in England. Her parents were rather wealthy and an aunt acted as guardian for both Frances and her younger sister Camilla until they came of age. Before her 20th birthday, Frances wrote A Few Days in Athens. Frances and Camilla went to New York in 1818 to watch a play that Frances had written called Altdor.

When Frances returned from England around 1820, she published a work called Views of Society and Manners in America. In 1821, she went to France to meet Lafayette, the Revolutionary War hero who had invited her there after reading some of her writings.

When Lafayette went to America in 1824, Fanny and Camilla went to America too, but not as official members of his delegation. They were with him when he was entertained at the homes of Jefferson and Madison. The winter of 1824-25 also included a meeting with Andrew Jackson, then a senator.

Since they were not part of the official delegation, they were free to move about on their own and traveled the U.S. extensively. During this time, they visited Robert Owen’s New Harmony Colony on the Wabash River in southwest Indiana where he was trying to establish a Utopian society. He believed that communal living would enable people to live happier, more economical, and more productive lives.

As a result of this visit, she decided to establish her own colony as an experiment to end slavery. She wrote: “The sight of slavery is revolting everywhere. But to inhale the impure breath of its pestilence in the free winds of America is odious beyond all that imagination can conceive.” She was equally fervent in her belief in the right of people to hold property, and so was searching for some way to free slaves without pulling the economic supports out from under the slave owner.

Frances submitted to Lafayette a plan for buying slaves, without loss to their owners, followed by life in a colony where they would be educated to be self-supporting and

prepared for freedom. She believed that slaves would work harder for their freedom than they would for a master, so free workers would be more profitable. She expected the colony to be also self-supporting and provide funds for the purchase and training of other slaves.

This was the plan discussed by former Presidents Jefferson, Madison, and Monroe and encouraged by Lafayette. Lafayette recommended Frances Wright to visit Senator Andrew Jackson. Jackson agreed to help Wright find suitable land and slaves and suggested that

Wright acquires land in the new Chickasaw purchase, approximately fifteen miles east of Memphis, which Jackson and his partners had founded six years before. It was decided that an area in Tennessee would be the best place for emancipation because public feeling there was more favorable to abolition than anywhere else in the south.

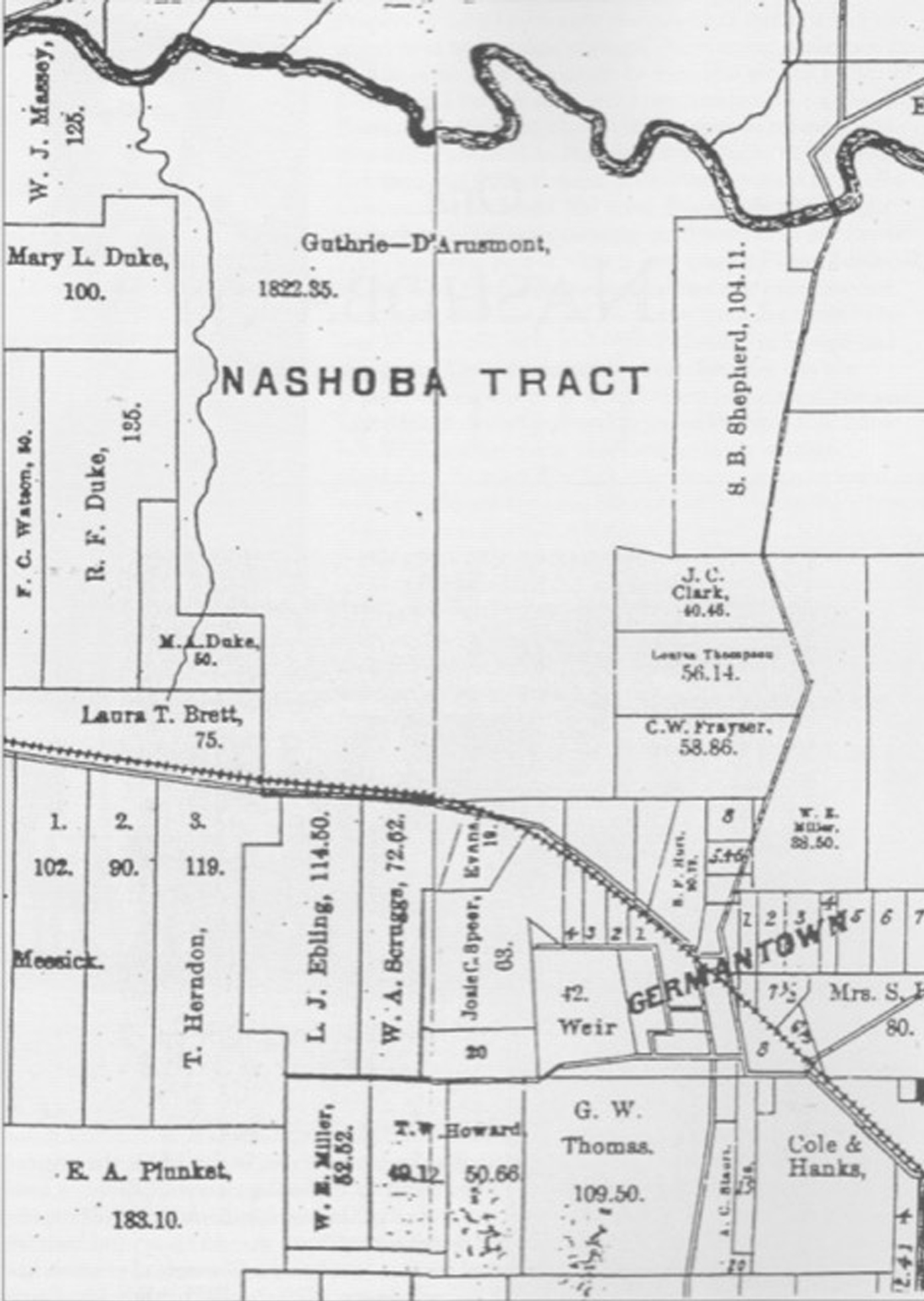

Frances rode horseback to Memphis, arriving late in October 1825, inspecting land along the Wolf River near the site of present-day Germantown. She then rode to Nashville, bought eleven slaves including five men (Willis, Jacob, Gradison, Redick, and Henry), three women (Nelly, Peggy, and Kitty), for $400 to $500 each, and three of their children. On the return to Memphis, she bought 320 acres for $480. She later negotiated for more property, eventually owning 1,940 acres.

Frances named her experimental settlement, Nashoba, the Chickasaw name for the Wolf River. She was only 30, she was rich and was applauded in Europe as well as the United States. Many approved her ideas because she offered hope of a way to prepare slaves to be self-supporting citizens while saving the South from the shock of the sudden loss of millions of dollars in investments.

Frances Wright was an admirer of Southern people who undertook the problems of slavery.

She wrote that she “knew from observation the evil effects produced by mere government abolition of evil, which has its seat in the mind, the habits and the very physical organization of a race.” Also, “To give liberty to a slave before he understands what its value is, perhaps, rather impose a penalty than to bestow a blessing.”

She described her land (Neshoba) as “2000 acres of good and pleasant woodland, traversed by a good and lovely stream (Wolf River), communicating 13 miles below with the Mississippi at the old Indian trading post of Chickasaw Bluffs.”

Part of the land was acquired by a grant from the state and part by private purchase. Marcus B. Winchester, Memphis’ first mayor, became a friend of Frances Wright, and his name appears as a witness on documents in connection with the establishment of her plantation.

She announced that Nashoba welcomed anyone, white or black, who was willing to work for the common good. Although Nashoba was an effort to end slavery, she envisioned a society in which cooperation, generosity, and freedom would reign.

Two men who played an important role in the experiment were Richeson Whitby, a shy Quaker from New Harmony; and a Scotsman by the name of James Richardson, who lived in Memphis and had strong convictions of moral freedom. A third was George Flowers who was an emancipationist with experience in utopian community living.

Frances was unaccustomed to physical labor, even though she was tall and walked with a manly stride. She and her sister moved to Nashoba and they worked beside the slaves who were on their way to freedom. Clearing trees, burning the underbrush, building fences, and planting an orchard, as well as building cabins. These tasks put calluses on their hands, weathered their complexions, exhausted their strength long before sundown, and exposed them to the fevers of the large part of the land that was in the river bottoms.

It broke Frances’ health. She became seriously ill with malaria and was encouraged to seek the milder climate of Ohio in May 1827. Camilla and Whitby were left in charge with Richardson to help.

But realizing that her plan lacked leadership, she had already deeded the property, land, and slaves, to a group of trustees in December 1826 under a deed of trust. The trustees were General Lafayette, William McClure, Robert Owen, C.D. Colden, Richardson Whitby, Robert Jennings, Robert Dale Owen, George Flower, Camilla Wright, and James Richardson.

While Frances was away, Camilla and Whitby fell in love and married, and passed the sterner tasks of leadership onto Richardson who took control of Nashoba’s policies. Critics believe that with Richardson at the helm, the Nashoba Experiment drifted from its original course of emancipation into a dangerous pool of radical ideas on communal living and moral unconventionalities.

The Wright sisters were inexperienced in the necessities of life in the wooded frontier since the South they knew best was Virginia. They found it difficult getting labor from illiterate workers, squelching quarrels among the field hands, and distinguishing illness from laziness.

Frances had gone on to Europe for her health and there she recruited Frances Trollope, an English travel writer. They returned through New Orleans and journeyed up the river to Memphis arriving in Nashoba on January 1828.

Mrs. Trollope was shocked by manners in Memphis, dismayed by desolation at Neshoba, and appalled by the primitive room in which she and Frances lived. She noticed the diet of pork and rice, without any other meat or vegetable, the absence of milk, butter, and cheese, and the fact that rainwater was the only liquid. She remained a few days and then hurried to Cincinnati.

Fighting gossip and criticism, waning support, and poor health, Frances Wright was no longer willing or able to struggle for the project. She went to New Harmony, Indiana, to work with Robert Dale Owen, the son of the founder of New Harmony.

She came to believe that the clergy were trying to hinder women from becoming educated. In 1828, Frances began her anti-clerical lectures to much controversy. She spoke on the abolition of slavery and on how religion was systematically repressing people from reaching their potential. Frances believed that after everyone became educated, they would have to see that slavery and the inequality of women were wrong.

Her plan had been to have five years of preparation prior to emancipation, followed by the establishment of a colony of Nashoba-trained men and women in Africa. The reality was that five years after she came to Memphis, she was putting 13 former slaves and their 18 children on a flatboat for New Orleans. Frances then chartered a vessel named the “John Quincy Adams”, sailing to Haiti in January of 1830 with the Nashoba slaves.

The newly freed former residents of Nashoba were placed under President Boyer’s supervision on one of his estates, rent-free, and supplied with tools and provisions. If they proved themselves worthy by becoming productive citizens, the former slaves were to be given land grants, enabling them to work their own land for the first time.

By 1830, Frances had climaxed a lecture career by her activities in the “Fanny Wright” political party, which actually elected a candidate to the New York Legislature.

She also announced her engagement to William S. Phiquepal D’Arusmont. Camilla died as a result of the trip to Haiti and Frances took solace in the arms of D’Arusmont, becoming pregnant. Faced with the way a child born out of marriage would be treated, she married D’Arusment and hid from public view, returning to England in 1830.

Later, on a business trip to America, Frances Wright broke her hip in a fall in Cincinnati and died there in 1852. So great was Frances’ national recognition as a public figure, through her political and oratorical activities, even William Cullen Bryant wrote an ode to her while he was editor of the Evening Post.

The heir to Frances property in Ohio and Tennessee was her daughter, Frances Sylva D’Arusmont, born 1832. Sylvia had come to America and being alone, lived in the family of Dr. Eugene DeLagertrie (or Guthrie) in Cincinnati. For convenience in handling her property, she deeded the Nashoba lands to Dr. Guthrie, who in turn contracted to furnish her a $5,000 annuity from them. To affect this he leased Nashoba to a tenant for a share of the profits.

After a time, Dr. Guthrie’s wife went to France to visit her family. When she had been gone some time there came the report of her death. Dr. Guthrie and Sylva were married in 1865 in New Jersey and had three children.

Sylva and her husband went to Europe – she to attend to property in Scotland, he to mend his health. While Sylva was in France, the Shelby County property stood idle, and lawyers raised questions about her title. Eventually, Shelby County Court canceled the unpaid taxes from 1861 to 1883, and the way was cleared for sales. She learned that the tenant at Nashoba had become the owner. Claiming breach of contract and many thousand dollars damage, he had asked the courts to sell the lands, and this had been done. Then he had taken them over from the buyer.

Sylva sued to have the court’s decree set aside, and in one of the most interesting and intricate cases on chancery records here, won back her heritage in 1878.

While there they also learned that the first Madame Guthrie was still alive. Dr. Guthrie’s health became worse, and he and Sylva went to Italy hoping that the climate would help. He died there.

The lands passed to her two sons, William and Kenneth Sylvan, who became ministers in New York City. They sold the property to Thomas Payne, grandfather of Postmaster Frances Hudson. He covered the original logs with weatherboarding as well as the dogtrot.

Mr. and Mrs. L.B. Lary bought the property in 1947 and remodeled the building, all but the foundation. The home then faced Riverdale rather than Poplar Pike. On February 9, 1979, the house still owned by Mrs. Lary burned. The house was located in what is known today as Nashoba Plantation, just west of the development’s entrance off Riverdale Road.

Son Kenneth had two children, Kenneth and Sylvia Camilla D’Arusmont. And Sylvia was the mother of the great, great-granddaughter of Frances Wright, Susan Guthrie Chang Saridakis, who contacted me and inspired these articles on Frances Wright.

Another Article from Monticello.org

Frances Wright (1795-1852), born in Scotland and orphaned at the age of two, rose from rather inauspicious beginnings to fame as a writer and reformer. She and her only surviving sibling, Camilla, lived with various relatives in England until 1813 when they returned to Scotland to live with their great-uncle James Mylne, a professor of moral philosophy at Glasgow College. Frances Wright gained access to the college library and thrived in this new environment. She read everything she could about America, including Carlo Botta’s history of the American Revolution (Storia della guerra dell’ Independenza degli Stati Uniti d’America, 1809), a work that Thomas Jefferson highly valued. Much to her uncle’s disappointment, she became determined to travel to America to see how the principles articulated in the Declaration of Independence were working out in practice.

In 1818, Frances and Camilla Wright left for New York. There Frances Wright anonymously produced and published Altorf, a play about the struggle for Swiss independence. The two sisters then traveled unchaperoned several thousand miles through many cities and the backwoods frontier. Upon her return to Britain in 1820, she received a letter from Jefferson thanking her for sending him a copy of her play. He praised the play for giving “dignity and usefulness to poetry,”[1] and she responded in turn, expressing her reverence for Jefferson’s “enlightened, active and disinterested patriotism.”[2] Eager to spread the news about the new social and political ideas established by the American government, she soon published her correspondence with Mrs. Rahbina Craig Millar in book form. Views of Society and Manners in America has become one of the most celebrated travel memoirs of the early nineteenth century. Wright was unabashedly enthusiastic about a nation she considered a guarantor of freedom and equality: “The prejudices still to be found in Europe, though now indeed somewhat antiquated, which would confine the female library to romances, poetry, and belles lettres, and female conversation to the last new publication, new bonnet, and pas seul, are entirely unknown here. The women are assuming their place as thinking beings, not in despite of the men, but chiefly in consequence of their enlarged views and exertions as fathers and legislators.”[3]

Though dismissed by the conservative press in America and England, Wright captured the attention of reformers such as Jeremy Bentham and Mary Shelley. It was in Paris in 1821, on Bentham’s business and her own, that Frances Wright met the Marquis de Lafayette. He too praised her work, and she became a participant in Lafayette’s clandestine intrigues in support of various revolutionary movements. At his insistence, she published her fictionalized treatise on the philosophy of Epicurus, A Few Days in Athens (1822).[4] Jefferson said the work was a “treat to me of the highest order,” and he filled seven pages of his commonplace book with excerpts from it. He wrote that “the matter and manner of the dialogue is strictly antient … the scenery and portraiture of the Interlocutors are of higher finish than any thing in that line left us by the antients; and, like Ossian, if not antient, it is equal to the best morsels of antiquity.”[5]

After an extended stay at Lafayette’s family estate La Grange during which Wright worked on a biography of Lafayette, Lafayette persuaded Wright to accompany him on his farewell visit to America in 1824. Lafayette referred to their relationship in father-daughter terms, and she helped him to maintain connections with the European network of liberal activists. She realized the anomaly of her position in the masculine world of politics: “I dare say you marvel sometimes at my independent way of walking through the world just as if nature had made me of your sex instead of poor Eve’s,” she wrote to Lafayette. “Trust me, my beloved friend, the mind has no sex but what habit and education give it, and I who was thrown in infancy upon the world like a wreck upon the waters have learned, as well to struggle with the elements as any male child of Adam.”[6] Wright must have been aware that their friendship had aroused gossip. There was a growing resentment toward Wright among members of Lafayette’s family that she had become too involved in his life or too important in his affections, and by the spring of 1824 she left for England. Wright had suggested that he legally adopt her to publicly clarify their relationship, but neither Lafayette nor the family would accept her suggestion. Wright finally agreed to follow Lafayette. Accompanied by her sister, she sailed on a different ship and traveled in a separate carriage. Although this provoked criticisms, Lafayette consistently expressed his desire to have Wright accompany him to political events and to meet his famous friends. On October 1, 1824, Lafayette wrote to Jefferson about this arrangement: “She [Frances] is Very Happy in your Approbation; for, You and I are the two men in the World the Esteem of Whom She values the most. I Wish Much, My dear friend, to present these two adopted daughters of Mine to Mrs Randolph and to You; they being orphans from their Youth, and prefering American principles to British Aristocracy, Having an independent, tho’ not very large fortune, Have passed the three Last Years in most intimate Connection With My Children and Myself, and Have Readily Yelded to our joint Entreaties to Make a Second Visit to the U.S.”[7] Jefferson answered that they “will no where find a welcome more hearty than with mrs Randolph, and all the inhabitants of Monticello.”[8]

The Wrights arrived at Monticello a day or two after Lafayette. Although they would have missed the initial meeting, they nevertheless managed to observe the reunion of the two veterans who had not seen each other for thirty-five years. Frances Wright remarked that she enjoyed “one of the finest prospects I ever remember to have seen” from a mountain “consecrated by the residence of the greatest of America’s surviving veterans.” She said of Jefferson that his “tall well-moulded figure remains erect as at the age of 20, and his step is as light and springy as tho it cd. bear him without effort up the steepest sides of his favourite mountains.” Struck by his physically weakened state, however, she lamented that “the lamp is evidently on the wane nor is it possible to consider the fading of a light so brilliant and pure without a sentiment of deep melancholy.”[9]

Not all members of the “full to overflowing” household were charmed by this curious visitor. A visiting cousin belittled Wright for being a “bluestocking.” Jane Cary was annoyed because “to Ladies she never spoke, except to Mrs. Randolph as her hostess, and to the youngest girl of the party, whom she noticed favorably as a mere child.” She could not resist adding that “the Frenchmen told many instances of her masculine proclivit[i]es—on occasions she wd. harrangue the men in the public room of a hotel and the like.” Jane Cary sympathized with George Washington Lafayette, who resented Wright’s influence over his father, and scrutinized her appearance: “In person she was masculine, measuring at least 5 feet 11 inches, and wearing her hair a la Ninon in close curls, her large blue eyes and blonde aspect were thoroughly English, and she always seemed to wear the wrong attire.”[10] Whatever the attitude toward her may have been, Wright later wrote Martha Jefferson Randolph that her days at Monticello had been among the most interesting in her life.[11] Camilla had caught a cold at Monticello, but the Wrights were presumably content to be detained there for a few days after Lafayette’s departure for Montpelier. Then perhaps inspired by Jefferson, the Wrights planned their own excursion to the Natural Bridge and Harper’s Ferry before rejoining Lafayette in Washington.

Later, when Lafayette headed to the South in late February, Wright decided to proceed across the Midwest and down the Mississippi River. Before rejoining Lafayette in New Orleans in April, she visited Robert Owen and the community he had established at New Harmony, Indiana. By this time, the personal and political voyages of Lafayette and Wright diverged. Wright became more interested in the cause of emancipation. In Views of Society, Wright noticed slaveholders’ humanity to their slaves, in which they took such pride, as being mere “gilding” on the chains of bondage.[12] In fact, Wright grew wary of Lafayette’s public acclaim by those who were slaveholders: “The enthusiasm, triumphs and rejoices exhibited here before the countenance of the great and good Lafayette have no longer charms for me. They who so sin against the liberty of their country, against those great principles for which their honored guest poured on their soil his treasure and his blood, are not worthy to rejoice in his presence. My soul sickens in the midst of gaiety, and turns almost with disgust from the fairest faces or the most amiable discourse.”[13] Wright must have discussed the topic with Jefferson. She wrote from Monticello that “Mr. Jefferson is very anxious that some steps which he considers as preparatory to the abolition of slavery at least in this state should be adopted this winter. You will find his plan (that which he proposed, in the Virginia legislature at the time of the revolution) /sketched/ in the Notes.” Wright accounted for the prejudice against miscegenation as an incentive for this active measure: “The prejudice whether absurd or the contrary against a mixture of the two colors is so deeply rooted in the American mind that emancipation without expatriation … seems impossible.”[14]

By the time Lafayette left for France in 1825, Wright had decided to stay in America to promote social reforms. Not long after her visit to Monticello, Wright implemented a practical plan to demonstrate to Americans the possibility of eradicating slavery. In some ways her plan resembled Jefferson’s own scheme for gradual emancipation. Slaves would be trained for a vocation while working out the cost of their purchase, their keep, and their eventual colonization abroad. After meeting Robert Owen and observing his utopian community at New Harmony, Wright began an experimental community on the site of present-day Germantown, Tennessee. She called her 2000-acre farm Nashoba, the Chickasaw word for “wolf,” and about thirty slaves were employed. Lafayette and Robert Owen served as trustees of the venture, and though Jefferson did not offer an endorsement of financial support for the project, his response was supportive: “at the age of 82. with one foot in the grave, and the other uplifted to follow it, I do not permit myself to take part in any new enterprises, even for bettering the condition of man, not even in the great one which … has been thro’ life that of my greatest anxieties.” He continued, “Every plan should be adopted, every experiment tried, which may do something towards the ultimate object. That which you propose is well worthy of tryal.”[15]

Wright eventually merged the idea of separate colonization of freed slaves with the advocacy of a biracial cooperative community as the way toward a solution, but the project never prospered. In addition to crop failure and bad luck, Wright’s overseer, James Richardson, published extracts from the plantation’s journal that publicized his relationship with a slave woman, an indiscretion that scandalized the public. Wright eventually responded to attacks of “free love” in the wilds with an article in which she boldly claimed that miscegenation might offer a solution for racial injustices in America; she restated her emancipation plan and attacked racially segregated schools, organized religion, and marriage.[16]

Nevertheless, the sexual issue only became more explosive and it frightened away most of her prominent American friends. In 1830 Wright abandoned the plan, a venture that cost her more than half her fortune and drove her to the fringes of American life. The slaves were transported to Haiti, where she made arrangements for their housing and employment.

Not easily discouraged, Wright sought refuge in Robert Owen’s community at New Harmony. It is an interesting side note that Robert Owen visited Jefferson in the spring of 1825. Owen had just announced to Congress that he wanted to help Americans in their pursuit of a “perfect system of liberty and equality,” and he proposed the guiding principles of New Harmony to be “union, co-operation, and common property.” If Jefferson was not impressed by Owen, his granddaughter Virginia Jefferson Randolph and her husband, Nicholas Trist, were captivated enough to almost join the community, and they became lifelong friends of Owen’s son Robert Dale Owen.[17] Whereas the Trists seem to have remained secret admirers of the community, Wright actively supported the communitarian principles.

In support of these principles, Wright became the first woman in America to edit a journal, initially the Harmony Gazette, and after moving to New York City in 1829, The Free Enquirer. She also became the first American woman to give a popular lecture series before an audience of men and women. Little escaped her attention: she condemned capital punishment, cited the dangers of intolerant religion, and demanded improvements in the status of women, including equal education, legal rights for married women, liberal divorce laws, and birth control. She traveled to most of the major cities of the East and Midwest, making an impressive appearance as “noble” or “masculine” depending on the observer, and sometimes wielding her sole text, a copy of the Declaration of Independence. Condemned by the press and the clergy as “the great Red Harlot of Infidelity” and the “whore of Babylon,” and often in need of a bodyguard, Wright nevertheless captivated large audiences with her commanding presence. Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge, whom Wright would have met at Monticello in 1824, captured the sense of scandal that accompanied Wright’s name. Ellen wrote from Boston: “Frances Wright has arrived in Boston to deliver a course of lectures which I hope no body will go to hear. the report is that she has mad[e] a sentimental arrangement with Mr Owen …. Miss Wright will probably not be noticed by any modest woman.”[18] In another letter she derisively stated that Wright is again troubling Boston “where she divides public attention with a Rhinoceros the first ever brought to the United States.”[19]

Wright’s educational proposals and her involvement in the working-class movement led to political action. So identified with the Working Men’s Party did she become that the candidates of this movement became known as “the Fanny Wright ticket.” Apparently believing that this identification would hurt the party in the elections of 1830, the Wrights returned to Europe. Camilla, her lifelong companion, died a few months later. The next year Wright married a French physician, Guillaume Phiquepal d’Arusmont, whom she had first met when he was teaching at New Harmony. Lafayette, who despite their long physical separations and changing political concerns, served as a witness at her marriage. Wright and her husband returned to America in 1835 to settle in Cincinnati, and once again, she began to give speeches. She became a convincing supporter of President Andrew Jackson and attacked the Second Bank of the United States as a public menace that bound the U.S. to the wealth of England. Her suggestions for gradual emancipation and the eventual assimilation of free blacks aroused much opposition, and her public appearances provoked demonstrations, even violence.

Wright traveled back and forth between the United States and Europe several times in a vain effort to untangle personal and financial affairs, and in 1848 she published her final book, England, the Civilizer, a utopian forecast of a global federation justly governed and united in peace.[20] By this time, however, Wright had moved from a largely uncritical view of America to a jaundiced attitude toward all society as a “complicated system of errors.”[21] Her views on America had been tempered, enabling her “to see things under the sober light of truth, and to estimate both the excellences that are, and those that are wanting.”[22] Wright seems to have spent her remaining years alone. D’Arusmont had objected to her return to public life, and frequent separations eventually led to their divorce. Her divorce was granted by a judge in Shelby County, Tennessee, while she was living on her Nashoba estate, and it actually made legal history. A judge in Cincinnati granted her petition for receiving $800 from her own property while the chancery court suit over control of her property was being decided. Her only child, Sylva, remained in her father’s custody, but by the time of Wright’s death in 1852, the chancery suit in Ohio was still unsettled, and therefore became moot, and her daughter was bequeathed the bulk of her estate.[23] Wright’s death went largely unnoticed. She was buried in the Cincinnati Spring Grove Cemetery.

– Rebecca Bowman, 10/96

References

- ^ Jefferson to Wright, May 22, 1820, in PTJ:RS, 15:612. Transcription available at Founders Online. See Worthington Chauncey Ford, ed., Thomas Jefferson Correspondence: Printed from the Originals in the Collections of William K. Bixby (Boston: The Plimpton Press, 1916), 254.

- ^ Wright to Jefferson, July 27, 1820, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Bixby Acquisition, Huntington Library. Transcription available at Founders Online. See Ford, Correspondence, 256.

- ^ Frances Wright, Views of Society and Manners in America (London: Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, and Brown, 1821), 422.

- ^ See Frances Wright, A Few Days In Athens: Being the Translation of a Greek Manuscript Discovered In Herculaneum (New York: E. Bliss and E. White, 1825).

- ^ Jefferson to Lafayette, November 4, 1823, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. Transcription available at Founders Online. See Ford, Writings, 10:282. See also Celia Morris Eckhardt, Fanny Wright: Rebel in America (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1984), 66.

- ^ Wright to Lafayette, February 11, 1822, quoted in Lloyd S. Kramer, Lafayette in Two Worlds: Public Cultures and Personal Identities in an Age of Revolutions (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1996), 158.

- ^ Lafayette to Jefferson, October 1, 1824, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. Transcription available at Founders Online. See Gilbert Chinard, ed., The Letters of Lafayette and Jefferson (Baltimore, 1929), 421-24.

- ^ Jefferson to Lafayette, October 9, 1824, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. Transcription available at Founders Online. See Chinard, Letters, 421-24.

- ^ Wright to Julia and Harriet Garnett, November 12, 1824, Garnett Letters, Houghton Library, Harvard University. See also Cecilia Payne-Gaposchkin, ed., The Garnett Letters ([Place of publication not identified]: Payne-Gaposchkin, 1979) and “The Nashoba Plan for Removing the Evil of Slavery: Letters of Frances and Camilla Wright, 1820-1829,” Harvard Library Bulletin 23 (1975): 221-51, 429-61.

- ^ Jane Blair Cary Smith, “The Carysbrook Memoir,” The Carys of Virginia, ca. 1864, Accession #1378, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library, pp. 72-74.

- ^ Wright to Martha Jefferson Randolph, December 4, 1824, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. Recipient’s copy available online.

- ^ Wright, Views of Society, 518. See also Lucia Stanton, “Looking for Liberty: Thomas Jefferson and the British Lions,” Eighteenth-Century Studies vol. 26, no. 4 (1993): 659.

- ^ Wright to Julia Garnett, October 30, 1824, quoted in Kramer, Lafayette, 162.

- ^ Wright to Julia and Harriet Garnett, November 12, 1824, Garnett Letters, Houghton Library, Harvard University.

- ^ Jefferson to Wright, August 7, 1825, Thomas Jefferson Papers, Library of Congress. Transcription available at Founders Online. See Ford, Writings, 10:344.

- ^ See Fanny Wright, Fanny Wright Unmasked by Her Own Pen: Explanatory Notes, Respecting the Nature and Objects of the Institution of Nashoba, and of the Principles Upon Which It Is Founded (New York: n.p., 1830).

- ^ Stanton, “Looking for Liberty,” 660-61.

- ^ Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge to Virginia J. Randolph Trist, July 21, 1829, Correspondence of Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge, 1810-1861, Accession #38-584, 9090, 9090-c, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. Transcription available at Jefferson Quotes and Family Letters.

- ^ Ellen W. Randolph Coolidge to Martha Jefferson Randolph, June 6, 1830, Correspondence of Ellen Wayles Randolph Coolidge, 1810-1861, Accession #38-584, 9090, 9090-c, Special Collections, University of Virginia Library. Transcription available at Jefferson Quotes and Family Letters.

- ^ See [Frances Wright d’Arusmont], England, the Civilizer: Her History Developed In Its Principles (London: Simpkin, Marshall & Co., 1848).

- ^ Frances Wright, Address on the State of the Public Mind and the Measures which it Calls for (New York: Office of the Free Enquirer, 1829), 9.

- ^ Frances Wright, Course of Popular Lectures (New York: Office of the Free Enquirer, 1829), 8.

- ^ David Bowman, “Frances Wright at 200,” Huntsville News, August 18, 1995.