Yellow Fever

Today, we live in a pandemic environment titled Coronavirus or COVID-19. Our ancestors lived through the Influenza epidemic of 1918. Their ancestors lived through the Yellow Fever epidemic of the 1870s. The experience of Sallie Eola Reneau, a nurse, and journalist, published accounts and reports of this deadly disease in Germantown.

By Andrew Pouncey

Germantown During the Yellow Fever

Sallie Eola Reneau’s Articles from The Appeal

Memphis Daily Appeal (Memphis, Tennessee) Wed. Sep 18, 1878

Germantown, Tenn.

From an Appeal Correspondent. Germantown, Tenn., September 16.

Our town is in unusual distress – eight deaths within ten days past, and there are now twelve to fifteen cases of the sickness of the same kind. I do not pretend to give a name to the disease which has proved so fatal, but I think fear and excitement, and the consequent lack of sufficient nursing have had much to do with the deaths, insomuch as the general health of the town and vicinity is far better than at this season of last year, when chills and malarial fever were almost epidemic, scarcely a family in which there was no sickness, and in some families every member was sick, but there were no deaths in the town and few in the country, because there was no excitement and no declared epidemic in Memphis, as now. On the fifth instant Professor R.B. Simmons of the public school, died of congestive chill, or yellow fever – reports conflict. On the twelfth, Willie A. Hunt, an excellent young man, barely grown, a son of Mr. B. F. Hunt, and formerly my pupil, died of congestion of the stomach, as reported, and as is reasonable to be believed, since he had been several years under medical treatment for dyspepsia. On the thirteenth darling little Mattie Lou Simmons, a two-year-old daughter of the late Professor Simmons, died of something fatal!

On the fourteenth Miss Mary O’Neil, Mr. James Harvey Rodgers, and Mr. John Walston, a Memphis refugee, died of something fatal! On the fifteenth Mrs. Moore, a Memphis refugee, and brother of Mr. W. H. Moore, secretary of Bluff City insurance company, died of yellow fever, as reported.

It matters not about the name of the disease, since the fatality, unprecedented in this usually healthful place, has become alarming to all who are not sustained by strong powers and unwavering faith. On the thirteenth “the storm” of excitement began to blow, and on the fifteenth, it burst in all the force of a general stampede of refugees and many citizens. Our railroad and express agent, who was also our telegraph operator, left us in haste. Our indefatigable postmaster and druggist, and principal merchant, Mr. Wm. E. Miller, Sr., remains faithful to his many duties and keeps his young son Willie at work with him; nothing but death or severe sickness will drive him from his post. He keeps his entire family at home, believing that they are as safe here as they would be elsewhere since the fatality is spreading through the country. I board in his house, and I feel that I am as safe as his family. Besides, the God on whom my faith is fixed rules in Germantown just the same as in any other place, and in no place can I hide from him – nowhere escape the life or death that he has appointed for me.

Among those who have thus far been faithful to the humane and Christian work of administering to the sick and burying the dead, Rev. R.R. Evans (Presbyterian minister), our principal physician, Dr. R.H. M’Kay, and his son James, Mr. Ralph Hicks, Mr. Jacob Roberts, Mr. A.J. Wright, Mr. A.R. Jacob Roberts, Mr. A.J. Wright, Mr. A.R. Hurt, the Messrs. Weir, Mr. J.G. Meacham and family, and Mr. Joseph Clark and family are prominent. There are also several colored men, whose timely help in buying the dead is worthy of remembrance. All who are brave and faithful during an epidemic and panic deserve special mention, for the temptation to fly or hide from danger and duty is surely great, and still greater and more demoralizing is the example of the many whose animal instincts of self-preservation is more than heathenish – quite brutish! An epidemic, like war, develops the latent strength or weakness, good or evil, of human nature, while it proves, by many sad pieces of evidence, that a coward cannot be a Christian or a soldier, and it revives, with humiliating force, the much-abused text: “A living dog is better than a dead lion.” Germantown has at no time taken part in the wicked farce of quarantine; all refugees and citizens have been, and are yet, free to come and go at will. All things, considered, our town has done remarkably well, and will continue to do the best she can; no town has done or will do, better. I hope the worst is over with us, as with all other communities. My school reopened favorably on the second instance, and worked smoothly until Friday last, when “the storm” of excitement broke into it; I shall have no school, of consequence, this week.

Sallie Eola Reneau

Germantown, Tenn.

From an Appeal Correspondent. Germantown, Tenn., September 18.

In my communication of the 16th, it should read seven instead of eight deaths within ten days, but as I gave the names, it is easy for the reader to make the correction. Your printer converted by nerves into powers, dyspepsia into dispepsia, and in several other instances perverted my “peculiar chirography;” but, knowing the many disadvantages under which he works, I can readily excuse him. The 14th, instead of the 17th, as you had it, was the day of the panic – the 14th of September 1878, a day-long to be remembered by the few who were left here to bury the dead, while the panic-stricken many were flying for personal safety, as if there is safety save in God, and as if God cannot save us here as elsewhere. I was present at three burials during the day, the greatest number of interments I ever witnessed in a single day. Someone remarked, during the interim between burying the first corpse and the second: “This is the anniversary of the declaration of epidemic yellow fever in Memphis in 1873.” At noon of the seventeenth, Miss Bettie Kelly died of bilious fever, as reported, at Mr. Bilbut’s, near Ridgeway station, two miles from Germantown, and was brought here for internment after sunset. She had resided here with a widowed mother and young sister until last May when the mother died, and the sisters found separate homes. Bettie was a good girl, distinguished in this community for neatness, industry, and devotion to an invalid mother through four years of weary watching and daily nursing. So few are the well ones left here to nurse the sick and bury the dead that there is no one to give notice, and no bells are tolled, when one is to be buried. When we see a light wagon and two or three persons passing slowly through the street, we instinctively recognize the wagon as the hearse and the few attendants as the funeral procession. If we desire to join that small procession we can do so, as it passes the house. Mr. Bibut and a young man with the wagon, preceded by Rev. Mr. Evans and Mr. L.A. Rhodes, with the colored grave diggers, already at the grave, constituted the force to bury Bettie Kelley. She and her little sister had been my pupils, and I felt that I owed her especial consideration; besides, I could not bear to think that a good girl, or any other woman, should go the grave unattended by a woman. I had never thought of seeing such a sight in Germantown, where until recently funerals have been few and attendants many; I gathered up my hat and ran after her, overtaking her at the grave, where, in the peaceful evening twilight, Mr. Evans offered a most feeling prayer, and we left the orphan girl with the ever-watchful stars to guard her grave, near the grave of her mother. The village churchyard, in the rear of the Methodist Church, is very near my place of abode and adjoining the beautiful three-acre grove in which my schoolhouse is situated; and it has not the awfully gloomy appearance of the average country graveyard. At nine o’clock this evening, 17th instant, Mr. Thompson Clark died of chronic diarrhea, much aggravated by fear and excitement incident to “the epidemic.” His being a decided case – decidedly not yellow fever – he had a large funeral attendance, consisting of fifteen persons. In his sickness, he had the devoted attentions of his brother, Mr. Joseph Clark, and the two families. Blessed Mr. Clark! It is a privilege “these times” to die of something else, anything else than “yellow-fever,” “that fever,” “the prevailing,” “the horrible scourge,” “the awful plague,” or the uncertain “it” – all of which names are odious and murderous, having murdered more persons during this season than disease has claimed for years.

Sallie Eola Reneau

Germantown, Tenn.

From an Appeal Correspondent. Germantown, Tenn., September 24.

I noticed that a correspondent writes from our little town about some of our best citizens, which was not necessary. He had no room to cut up. The reason he does not like the piece of which Miss Sallie E. Reneau wrote to the Appeal, was because there was not anything said about him. Yes, there ought to have been something said about him. He did so much, and this is what he did; he went after one coffin and carried it to the graveyard. Could not get him to go into the room where the sick person was, and the only thing he had to say about our friend A.J. Wright was, that he would credit him for a French harp. Now if he has got any room to get mad, I don’t see it. He also said something about our friend W.E. Miller, our only druggist, about staying so close, he had to stay close; he had no time to go and see the sick; he had to stay there to sell medicine for the sick. Mr. Miller is a perfect gentleman. Oh! I am about to leave out our good old beef man, Hon. Joseph G. Meacham, who left on account of his family. Mr. Meacham comes back every day to see us beef. I would like for you to see your writer of the twenty-third instant; he loves too much “John Barleycorn;” your town knows something about him, or the chain gang does; I could tell you more about him but will not at present – he’s all bluff. Mr. Miller is one of the best merchants in this place. I will give you the new cases that are in this little town: Mrs. E.U. Gorman, whose husband just go out of bed a day or two ago; Mrs. Simmons, her husband, and daughter departed this life not long since; they went to a better land. Mr. Simmons was a Methodist minister. Mr. Billy O’Neal has also got the fever; Mrs. and Mrs. O’Neal had just got up; his sister died with the fever. Mrs. T.C. Clark and Mr. Clark died last week. Mrs. B.F. Hurt lost her son on the seventh of September, Willie A. Hurt, who was barely grown. All else doing well. Please do not throw this in the wastebasket, for I want to show the people how wrongfully your writer talked about our friends; it was uncalled for.

Sallie Eola Reneau

Germantown, Tenn.

From an Appeal Correspondent. Germantown, Tenn., September 25.

As a matter of interest, I sent you a list of the officers of the committee and contributors to the Germantown relief fund, as follows:

Officers.

L.A. Rhodes, chairman; A. J. Wright, treasurer; R.R. Evans, secretary.

Subscriptions.

L.A. Rhodes, A.J. Wright, S.C. Garner, W.E. Miller, A.N. Plunkett, W.F. Sain, F.M. Howard, G.W. Thomas, L.P. Feathersten, N.F. Harrison, S.R. Maclin, M. Neely, W.D. Holder, J.M. Brett, G. R. Tuggle, Mrs. Eliza Callis, Mrs. Lucy Cogbill, Miss S.E. Reneau, Wm. Carter, J.A. Thompson, J. Brooks, R.A. Adkins, W.J. Robbins, J.W. Wells, W.H. Myrick, R.R. Evans, E.W. Gorman, C.M. Callis, M.M. Alexander I. Stout, J.H. Alsup, N.M. Alsup, H.T. Jones, J. N. Snowden, Hill, Fontaine & Co, H. Dow, J.P. Hoffman

Of the white population of Germantown and vicinity, there is but one dependent family, and that family has required very little material assistance; hence, the relief committee is in receipt of funds sufficient for present purposes. The citizens are prepared to contribute whatever amount may be required unless visited by affliction far greater than the community has yet suffered. The committee has not asked nor received assistance outside of the community. Two nurses were sent, as they said, by the benevolent Howard Association to Memphis, but as their services were not required, and the committee had not called for them, they were immediately dismissed.

Death List

September 5 Prof. R.S. Simmons, citizen.

September 12 Willie A. Hurt, citizen.

September 13 Mattie Lou Simmons, child of the late Prof. R.S. Simmons.

September 14 Miss Mary O’Neil, citizen; Mr. Jas. Harvey Rogers, citizen; Mr. John Watson, of Memphis

September 15 Mr. Henry J. Moore, of Memphis

September 17 Miss Bettie Kelley, former citizen, died at Ridgeway, Mr. Thompson Clark, citizen.

September 18 Miss Jennie Johnson, citizen.

September 19 Miss Sallie Bet Shepherd, citizen.

September 21 Mr. J.C. Buster, citizen.

Of the sick, Mrs. Thompson Clark and Mrs. Simmons, widow of the late Prof. R.S. Simmons, are in a critical condition, but there is hope of their recovery. All the other cases “doing well.”

Sallie Eola Reneau

Germantown, Tenn.

From an Appeal Correspondent. Germantown, Tenn., September 28.

Hope, taking advantage of the four days absence of Death, reigned in our community with levity until the night of the twenty-fifth instant, when Death returned to reassert his rule and to number among his victims Mrs. B. F. Hurt, the beloved wife of Mr. B.F. Hurt and the honored mother of eight living children. Besides her many excellent virtues as wife and mother, Mrs. Hurt was remarkable for personal beauty, refined taste, and love and culture of flowers. The language of flowers to her was the expression of the conviction of her mind that her physical form, for many years diseased, was as frail as her beautiful flowers, and like them, must pass away. It is not amiss for me to say that no school patron has ever given me more encouragement than Mrs. Hurt, in her quiet, sincere way. In her last sickness, she received every care and attention from her physician, Dr. J.A. Thompson, her husband, four of her sons (two being absent), her son-in-law and her daughter – Mr. and Mrs. Carpenter of Collierville – her other daughter, Mrs. J.H. Clark, of Collierville, being unable to attend her. Mr. Hurt, Mr. and Mrs. Carpenter, their little daughter Katie and the colored cook were left homesick when the four sons and a sufficient number of friends follower her to the grave and laid her down to rest with the son whom she followed to the grave only thirteen days previous. My bright and beautiful pupil, little Nellie Gorman, the six-year-old daughter of Mr. E. W. Gorman, died and was buried on the twenty-sixth instant. Nellie was an unusually intelligent and sprightly child in school and out, and she was a little sunbeam in her family household. There are few ties, stronger and tenderer than that which binds a fond father to his only daughter, and it was peculiarly touching to see the bereaved father, just up from an attack of the fever, though accompanied by a sufficient number of friends and the ever-faithful minister, following his little girl to the grave, while he left sick in his house his wife, his little son June, his wife’s sisters, Miss Ellen Edmonson and Mrs. Rogers (whose husband died at Mr. Gorman’s, on the fourteenth) and their niece, Miss Willie Allen. This family has received kind attention from Mr. Joe Weir and Mr. Lee Rainey. Dr. R.H. M’Kay and several of his children have been quite sick for several days. Mrs. John Walston, of Memphis, is also sick in the doctor’s house. The community is anxiously hoping to see the good doctor well and out again. There was cause for discouragement and gloom when it was announced that Dr. M’Kay was down, and Dr. Thompson was left alone to contend with the disease, which was spreading to such an extent that it became necessary to call for help. The Howard Association of Memphis sent Dr. Bryant, of Texas, and four colored nurses, all of whom arrived by the afternoon train of the twenty-sixth instant. The nurses were distributed to Mr. Hurt’s, Mr. Gorman’s, Dr. M’Kay’s, and Mr. J.C. Clark’s. Mr. Clark’s sister-in-law, Mrs. Thompson Clark, has been quite sic, in his house, for a week. She has been faithfully nursed by the family, and it is hoped she will recover. Mrs. Simmons, with the excellent nursing of her mother, Mrs. Booth, who is said to be “as good as a doctor” and the additional care of her brother-in-law, Dr. Malone, of Capleville, has a prospect of recovery, though still reported in a critical condition. Mr. Lee Rainey, who has been quite active in his services to the sick, is now at the mercy of the disease, but as he has the invaluable nursing of Mr. Joe Weir, and his (Mr. Rainey’s) mother to encourage him, it is hoped that he will soon recover. With due deference to all other human help, there is nothing like the tender, watchful care of a good mother. When an experienced nurse was offered to Mrs. Both, by the secretary of the Relief Association, she declined the offer, preferring to give her own attention to her daughter. Mrs. Weir, another good mother, by unremitting care, has brought her daughter through a severe attack. Mrs. Lettie Bridges, with the assistance of her brother, Mr. Robert Scruggs, has nursed her little ones, Nannie and Henry, into health.

Sallie Eola Reneau

Germantown, Tenn.

From an Appeal Correspondent. Germantown, Tenn., October 3.

The following is the complete death roll of Germantown to date. All of the persons named were citizens of the village:

Prof. R. S. Simmons, Mattie Lou Simmons, James Harvey Rogers, Thompson Clark, Miss Sallie B. Shepherd, Mrs. B.F. Hunt, Dr. Robert H. M’Kay, B.F. Hunt, Sidney Carpenter, Tommie Hurt, Lee Rainey, June M. Gorman, John Walston, Memphis, Willie A. Hunt, Miss Mary O’Neil, Miss Bettie Kelley, Miss Jennie Johnson, J.C. Buster, Nellie Gorman, Mrs. Thompson Clark, Miss Ellen Edmonson, William E. O’Neil. Miss Willie Allen, Mrs. Sallie Walker, Robert Lee Hurt, H. J. Moore, Memphis. Total, 26, All white.

In proportion to population, no community has suffered more severely than Germantown, and no town in the fever district could have less local cause of disease. For five years prior to the beginning of the present epidemic season, the deaths in this healthful place have not averaged two per annum. There was hope and a prayerful desire that Mr. Lee Rainey’s life would be spared to the community, to which he had become so useful and necessary in this season of severe trial. His condition was so hopeful for several days that it was with surprise and grief we received the report of his changed condition, then of his death. He leaves a bereaved mother, wife and child, and a large circle of sorrowing friends and relatives. Mrs. Walker’s death was unexpected. She had borne her trials – the death of their granddaughter, and the sickness of her son and grandson – so well, relying on God for strength to bear whatever burden He might put upon her, that it was hoped that by the remarkable vigor of her mind, and her unusual physical strength for one of her age, and her christian faith and fortitude, she would be upheld and supported. But, under the pressure of this unprecedented season of distress, the silver cord of life was loosed, and a mother in Israel was removed from the remnant of her race. No woman can fill Mrs. Walker’s place; nor person will be more missed than she, who was friend to white and black, to everyone who would be befriended. June Gorman, my excellent little pupil, is the fifth member of his family to cross the threshold of death in the short period of eighteen days. He leaves a sick aunt, Mrs. Rogers, and his mother in a critical condition God knows – man can never know – the sorrow of that afflicted mother. Bobbie Hurt, who was my kind and pleasant pupil for several years, is the sixth member of his family borne to the grave within twenty days. He leaves a brother and sister lingering on the verge of the grave. Was ever a family in Grenada or Memphis more afflicted? Mr. Albert Hurt is the only member of the family able to be up. His little niece, Kate Carpenter, has recovered. The good father, from Memphis, a refugee at Mason, Tennessee, who wrote me on the twenty-sixth instant, inquiring the whereabouts of his son, need offer no apology for so doing. It gives me pleasure to convey intelligence when the intelligence conveys happiness to the inquirer. I have answered his anxious letter by postal card; but lest it should be delayed by irregularity in mails, I may say here that his son’s mail is, by the son’s order, forwarded from this office to Monticello, Hardin County, Tennessee. I doubt not that his son has written, and his letters have failed to reach the father.

Sallie Eola Reneau

Germantown, Tenn.

From an Appeal Correspondent. Germantown, Tenn., October 6.

Howard – Visitor Rogers telegraphed the Howards from Germantown, yesterday, that the last resident physician was down sick, and that the physician (name not stated) who went there yesterday had been stricken with the fever. Another physician and three nurses are badly needed.

Germantown, Tenn.

From an Appeal Correspondent. Germantown, Tenn., October 14.

There has been sixty-five cases of the yellow-fever and twenty-nine deaths since the first of September. The last three being Mrs. L.A. Rhodes, who died October 11th. She was a good, pious woman, charitable, and one of the best of mothers. Mrs. W. E. Miller died October 12th; a christian mother and a kind wife. Mr. L. A. Rhodes died October 13th; a noble-hearted man, a good father, a kind husband and a worthy citizen in every respect. There are still ten convalescents. No new cases. I hear of Miss Sallie Reneau’s death, a most intelligent lady.

RENEAU – At Germantown, Tennessee. October 18, 1878, died of yellow fever, Miss Sallie Eola Reneau, daughter of General N.S. Reneau, of Washington City

The deceased leaves a large circle of friends throughout the Union who will mourn her loss. A woman of great mental endowments and rare intellectual attainments, she leaves her impression upon the minds and hearts of those who were favored in being her pupils, as well as upon her associates and friends. The motto of her life was “Universal love to all mankind,” and like many others at this hour, she laid down her life for her neighbors and friends. “Verily, Death loves a shining mark.”

Mizpath

Germantown, Tenn.

From an Appeal Correspondent. Germantown, Tenn., October 20.

The death on Wednesday last, of Miss Sallie E. Reneau, daughter of General Reneau, was acknowledged the greatest calamity that has befallen the little town of Germantown, where she proved herself among the most capable of nurses, the truest and staunchest of friends, and an angel of mercy to the fever-stricken poor during the epidemic. A lady of cultures and refinement, she enjoyed the love and respect of her neighbors, who mourn her death as a loss personal to each one of them. Her letters to the Appeal were among the most readable and reliable of our extensive correspondence and were always welcomed by our readers. Her father and family have our sincere condolence upon a loss which the community shares with them.

Biography of Sallie Eola Reneau

Sarah Eola Reneau, known as Sallie, was born on August 1, 1836, in Somerville, Tennessee. Sallie’s brother, Captain William Edward Reneau of the Confederacy Army, was killed in the Civil War.

Her father was General Nathaniel Smith Reneau, born July 10, 1814, who served in the Mexican War from Tennessee and was mustered out at Vera Cruz on “surgeon’s certificate.” He was a colorful man who had been in the railroad industry. Upon selling his interest, he invested in large silver mining interests in Mexico. He was well-known in Washington in connection with Mexican affairs. He had large international interests there and for some months had enjoyed close relations with the President and the Mexican Minister in regard to diplomatic relations with that country. General Reneau spent much time in Washington, D.C., although he made his home in Batesville, Mississippi.

The General has been notable for efforts for the relief of the unfortunate people of the South, but more especially for those of Mississippi. Every few days Gen. Reneau would exhibit a letter from his daughter and would use her eloquent and touching descriptions of the trouble that was around her, as his excuse for more urgent appeals for help.

Sallie was a crusader for state-supported higher education for women in the South. Sallie Reneau of Panola County, Annie Coleman Peyton of Hazelhurst, and Olivia Valentine Hastings of Port Gibson campaigned for several decades before and after the American Civil War (1861-1865) to persuade Mississippi politicians to support a college for women equal to The University of Mississippi (1848) and Mississippi State University (1878), both established for the education of white men.

Sallie was the founder and President of Reneau Female Academy, which later, with the assistance of Annie and Olivia, became The Industrial Institute and College for the Education of White Girls, then later the Mississippi State College for Women, and now Mississippi University for Women at Columbus, Mississippi, at Columbus, Mississippi. Reneau Hall, at this college, is named in her honor. “She had devoted her life to the education of her sex, rich and poor, having been a distinguished scholar and educator.”

Sallie was a remarkable woman and, when the yellow fever epidemic broke out in West Tennessee, she went and volunteered her services as a nurse and historian of the ravages of the disease, as her published accounts and reports now before us testify. She was a leading spirit in the organization and management of all relief and charitable movements of the place where she had voluntarily determined to do her best for those who suffered around her.

Sources:

Photo and The Appeal, Fall of 1878 (Commercial Appeal): http://www.mshistorynow.mdah.ms.gov/articles/379/the-history-of-mississippi-university-for-women

https://sites.rootsweb.com/~nwa/reneau.html

Yellow Jack in Germantown

By Linda Fitzgerald Scott

The 1870s began as a period of growth for Germantown with the population increasing from 197 in 1870 to nearly 400 residents by 1878. 1 The 1873-74 Tennessee State Directory printed this list of businesses and professional people in Germantown.

“T.P. Chambers, attorney; R.R. Evans, minister, B.F. Hurt, cotton gin; A. Johnson, boarding house; W. Madison, grocer; R.W. Martin, physician; R. H. McKee, physician; William Miller, druggist; Rhodes & Son, general store; Sherrard & Walker, general store; R. W. Scruggs, general store; J. Thompson physician; A.J. Wright, grocer. 2

Some people moved to the area seeking a fresh start after the Civil War. Thaddeus Milton Howard, a Confederate veteran originally from Iuka, Mississippi, moved his family to Germantown in 1872, hoping for a prosperous new life. George W. Thomas, a Mississippi native, and a Confederate veteran, also chose Germantown as a place to raise five sons and four daughters. He became a prosperous merchant in the town and eventually owned 1,000 acres of land. 3

Arthur O’Neil’s story was different. He was born in Ireland, raised in Scotland and was assigned to the Royal Guards to protect the British royal family. Irish by birth, his sentiments were never with the British royalty and in 1849 he ran away to the United States. When his fortunes improved, he sent for his sweetheart Bridget, and his parents. 4

By the 1870s, O’Neill, his wife, and their children were living in Germantown. Dressed in stiffly starched and ruffled shirt, he worked as a wheelwright, laboring at the bellows in his workshop turning out iron-rimmed buggy wheels. The shirt was more than fashionable. Sparks from the fire would bounce off the starched garment and not burn through to his skin. He loved to sing Irish songs and recite the poems of Robert Burns. O’Neill and his family attended the Methodist Church. 5

Many of Germantown’s new residents came from Memphis. After the war, Memphis was preoccupied with growth and bustling commercial activity. Unfortunately, aesthetics and good hygiene took a back seat to making money. As a result, city streets filled with garbage, sewage, dead animals, and putrid water, the stench of which was unbearable. 6

Memphis suffered a yellow fever outbreak in 1867 and a reoccurrence in 1873. Residents breathed a sigh of relief with the first frost of 1873. A heavy frost and cooler temperatures had always marked the end of new yellow fever cases, but people relaxed their vigilance too soon. In the midst of a cold spell, a violent outbreak of smallpox struck. In the spring, the beleaguered city fought a cholera outbreak. A newspaper account indicated that 59 people had died of cholera by June 25, 1873. 7

An equine disease, epizootic, also hit Memphis hard that same year. The exorbitant number of sick and dead horses crippled the city’s horse-drawn transportation. 8 With an array of ills in Memphis, many residents relocated to Germantown. The countryside was perceived as a healthier environment and it certainly smelled better. 9

William Carter subdivided his 493-acre Germantown plantation in 1872 to accommodate the influx of new people. Carter’s plantation was located on the east side of Germantown, south of the railroad tracks. Carter’s home, originally built in 1854, was located on lot three of the subdivided property. 10

By May of 1878, people were focused on getting new crops planted and securing ample merchandise for flourishing businesses. Growth and prosperity were evident everywhere, as was the smell of fresh lumber and the drum of hammers as new homes and businesses took shape.

In the midst of such optimism came ominous news that a yellow fever epidemic was raging in the East Indies.11 Within two months, the disease would begin its siege of New Orleans. The July 26 newspapers indicated that yellow fever cases had been on the increase for two weeks in that city. Apprehension grew when yellow fever broke out in Grenada, Mississippi on August 10th.

There was little doubt the fever was heading north. 12 Quarantine stations were established along the railroads leading to Memphis, including one at Germantown on the Memphis and Charleston Railroad. Anyone coming from one of the infected areas or appearing ill was turned away. A quarantine station was also set up at the southern point of President’s Island to check river traffic. Railroad and steamboat officials promised to carefully scrutinize all passengers and baggage coming aboard their transportation systems.13

Precautionary measures did nothing to deter the fever. By the time these steps were taken, yellow fever had already arrived in Memphis. Its mode of travel was the river, not rail. A boatman, who had traveled upstream by steamboat to Memphis, died of fever at the Memphis City Hospital. On August 14, the death of Mrs. Kate Bionda, the owner of an Italian snack house catering to boatmen, was announced. She was the first confirmed yellow fever case originating in Memphis. Within two days, 65 new cases were discovered in Memphis. By August 23, the fever reached epidemic proportions with hundreds of deaths reported. 14

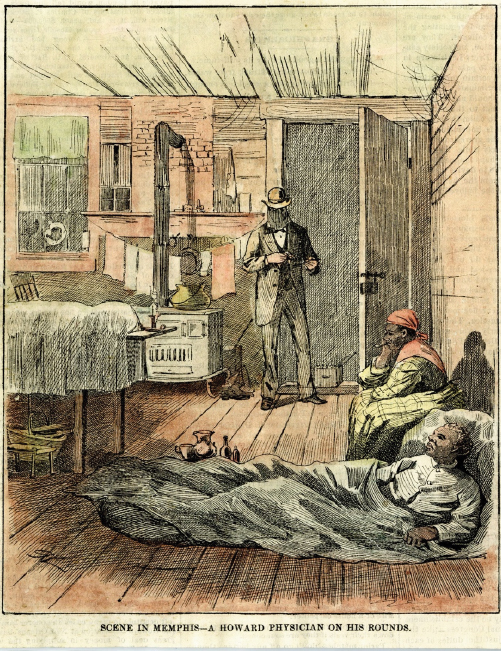

Doctors and nurses, volunteering through the Howard Association, brought medical care and much-needed supplies to the stricken area. The Association originated in New Orleans during the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1853 among the clerks of the N.B. Kneass Company. The mother of two of the young clerks had lived in San Domingo where yellow fever was common, and there she learned the most effective ways of treating the disease. When the epidemic hit New Orleans, her two sons traveled around the city distributing medicine prepared by their mother. Others joined them in their humanitarian task. They named their organization after philanthropist John Howard. The Association furnished doctors, nurses, medicine, and supplies to towns threatened by yellow fever. Their volunteers came from all over the country. 15

The fear of yellow fever was heightened by the fact that no one knew what caused it. Some claimed that it was due to unsanitary conditions. Dr. Thomas Summers hypothesized that it was caused when heat and moisture conditions reached favorable levels for the growth of germs. Others claimed yellow fever was God’s punishment for the annual celebration of Mardi Gras, which Memphis had initiated in the early 1870s.16

The true cause of yellow fever would not be known until 1900 when Dr. Walter Reed discovered it was transmitted by the bite of the Aedes aegypti mosquito. Apparently, the epidemic in Memphis began when a mosquito or mosquitos fed on the blood of the infected New Orleans boatman and carried the fever on to a new, ever-widening set of victims. 17

In Memphis, protection against the dreaded disease was flight. Thirty thousand of the city’s 50,000 residents began a frantic exodus out of town, over 2,000 died within the first three months. By August 25, an official with the Board of Health reinforced the panicked desertion of homes, jobs, and neighborhoods, by advising anyone remaining to vacate the city. 18

Trains were unable to accommodate the mass of people attempting to board. Even after all seats were filled, desperate escapees continued to crowd into aisles, platforms, and on roofs of train cars. Some even made desperate attempts to climb through the windows of the packed trains.19 Those who couldn’t take the train left any way they could, by carriage, buggy, wagon, dray, and even on foot. Many had no clear destination other than to put distance between themselves and the fever. Even animals abandoned the city and its aura of death. Cats, dogs, and rats were nowhere to be seen during the epidemic. 20

On August 17, news indicated that the suburbs and countryside outside Memphis were filling up with refugees from the city. By August 21, the quarantine stations that once worked to prevent people from entering Memphis, now worked to keep people from leaving. Fear motivated people in nearby towns to set up their own “shotgun quarantines.” Townsmen, emboldened by guns and sulphur in their shoes to ward off the fever, turned back people fleeing Memphis. Many of these people who were unable to escape the city or unable to find a community to take them, lived in refugee camps set up outside Memphis. 21

Germantown had its share of yellow fever refugees. Be September 29, 1878, Germantown officials notified the Howard Association that 20 people in the community were suffering from yellow fever. They made a desperate plea for badly needed supplies and ice to treat the feverish 3 patients. The Howard Association compassionately granted the request even though it had its hands full in Memphis. 22

At his estate just south of Germantown, Dr. Leonidas Polk Richmond fought to save fever victims, just as he had worked to save battle victims during the Civil War. In order to protect his own family from yellow fever contamination, he isolated himself, living in his small office building located at the forefront of the property. His meals were left on his office doorstep, unclaimed until the deliverer was out of sight. Whether by the fruits of his efforts or by simple luck, he and his family were spared the fever. 23

William E. Miller, the Germantown druggist and postmaster from 1872 to 1878 was stricken with fever. He had worked day and night to mix medicines for other fever victims. His wife died October 12th and he followed on November 16th. Two sons and a daughter were left without parents. 24

The Reverend R.R. Evans, whose efforts saved the Presbyterian Church during the Civil War, also became an unintentional hero during the epidemic. His diary, written in combinations of English, Greek, and his own personal shorthand, documented yellow fever in Germantown. Evans led secret burial parties at night to prevent widespread panic in the community. 25 His discretion was well warranted. According to the Memphis Avalanche: “In the county, one case of fever generally causes a stampede of the entire community.” 26

Everyone was afraid of catching the fever and most didn’t want to get near the desperate victims to help. However, Arthur O’Neill, the colorful Irish wheelwright, helped everyone in the Germantown community is stricken with fever but never caught it himself. He did not go untouched though, losing a daughter, Mary, to the fever. 27

In an effort to prevent panic among his neighbors, O’Neill sought to hide her death. An elderly, Black man, identified only as “Jim”, bravely assisted O’Neill. At night, he drove a spring buggy to the back of the house and lifted Mary’s coffin through the window and into the buggy. She was unceremoniously buried, without a funeral or monument. Mrs. Mary Scruggs, one of “O’Neill’s children recalled that she and her siblings reproached their father over the lack of a monument for Mary. O’Neill made it clear that monuments were not necessary. “We were told to so live, that our lives would be a monument after we had gone.” 28

Even with yellow fever present in the community, the countryside still was preferable to Memphis. Mrs. William H. Stovall took refuge at a farm just east of Germantown. 29 On October 8, 1878, Mrs. Stovall’s sister, Bettie, who remained in Memphis during the epidemic, wrote of conditions there:

“We all continue well, very well, but our anxiety is very great. Of course, you see the papers and know pretty much the fearful conditions of our city. I do so much wish we were in a place of safety. I don’t think of going out. All-day I stay right here, week after week, and see no one, go nowhere…Aunt Lamina’s family have all left town. Laura and I are now more in danger than any of the family. There are a good many cases close around Georgie. Miss Octavia Yancey is one of them. The evening paper gives 80 deaths since 1 o’clock yesterday [sic]. We see funerals pass all day long.” 30

On September 20, Memphis officials sent a telegram to New York, pleading for additional assistance. At that time, 2,250 dead, 3,000 sick, and another 10,000 destitute souls were being fed in camps. The telegram ended, “We are praying for frost: it is our only hope.” 31 A young Ohio volunteer wrote home of the horrors in camps outside Memphis: “I am completely broken down. I have not slept for six hours since I have been here…A million a minute, and the interest on it would not tempt me to take another trip of this kind. Only for

humanity’s sake I came, and I don’t regret it, but I did not expect to find putrefied bodies all around me, and people dying from neglect. I pledge you my honor I have not seen a case cured yet. It is the Plague. 32

On October 29, the Memphis Appeal ran an editorial celebrating that the frost had come. 33 By the end of the epidemic, about half of Germantown’s population was gone, either dead from the disease or moved away to escape it. 34 Although record-keeping was sketchy, Keating’s History of the Yellow Fever indicates that 43 people died in Germantown. In some instances, victims were entire families, among them six members of the B.F. Hurt family and the Reverend and Mrs. R.S. Simmons, and daughter, Mattie Louis Simmons. 35 Such incidents were common occurrences, according to Keating:

“One of the remarkable features of the disease, as it prevails now, is that whole families have been swept out of existence – father, mother, and children have followed each other in rapid succession to the grave, and in some instances several members of the family are lying dead at the same time, having died almost within the same hour.” 36

In Germantown, the fever also took those who nursed the sick, as in the case of Dr. R.H. McKay. Civil War veterans H.R. Moore and John 37 The epidemic had brought a flurry of trade, construction, and planting to a halt. Businesses had closed in Memphis and activity by planters and country merchants ceased. Cotton had not been picked nor transported to market. Even the tollgate keeper on the road had stopped collecting fees because travel had dwindled to a few doctors and nurses or those transporting coffins. 38

Germantown had suffered through two difficult periods: first the war, then the fever. With a population cut in half and commerce frozen, residents were eager to return normalcy to their community. 39

Almost a year after the community put its fever victims to rest, fears of a new outbreak loomed in Germantown as news spread of a second epidemic in Memphis. The Memphis Yellow Fever The epidemic of 1879 began in May and last until November 10th but seemed to be milder than that of the previous year. Of the 2,010 cases reported in Memphis, 587 were fatal. Germantown and other towns were spared, thanks to lessons learned during the previous epidemic. The State Board of Health strictly endorsed recently passed quarantine laws to prevent the spread of fever to nearby towns. 40

A youthful impression of the fever aftermath was given by a schoolboy of the time, Platus Iberus Lipsey, son of the Reverend John Washington Lipsey, who served as minister to the Germantown Baptist Church and the Collierville and White Station Baptist churches in 1879:

“In 1879 the Yellow Fever came back to Memphis and the people in Germantown were terrified at the first news. When it became known, we six children were at home without father and mother, left in the care of an old maid, Miss Emily Clark, who had been through the trying period of the year before. She belonged to a large family of good people, poor, most of whom, survived the plague of 1878. Father and Mother had gone for an extended visit to friends and relatives in Arkansas. The very day they passed through Memphis the fever was announced. I cannot forget the look on peoples’ faces in the afternoon when the train came bearing the afternoon papers with big headlines: “THE SCOURGE AGAIN!” Peoples’ faces were blanched and set, and they began talking about experiences of the year before. That night we children listened to Miss Emily’s story of the dreadful things that passed through twelve months before. Death seemed to be stalking us. Father and Mother soon returned, and we settled down to41

Although Germantown was spared in 1879, the yellow fever epidemic of 1878 would not soon be forgotten. A void existed, created by the loss of many family members and neighbors. Those remaining must have been stricken by the fragility of life and their own good fortune to be among the survivors. People turn to the support of the community and the church. Lipsey recalled a church gathering held in the wake of the 1879 scare:

“Father soon began a revival meeting in the church at Germantown which lasted for four weeks, and over forty men and women were baptized. It was, I think, the greatest meeting of my boyhood days. The first week was rainy and bad, but people kept coming. The second week the weather broke, and the blessing came. Day and night the power of God was present to serve. There was no great excitement, but deep earnestness. I have never seen so large a proportion of mature men saved. It was a happy time. Of course, a few sneered and said, “Yellow Fever converts,” but the work of grace spread…I recall the big baptizing down at the Wolf River a mile north of town. When Mr. F. Scott came up from the water, his long beard was like a halo about a

happy face and I heard him say, “Thank God for the first duty done?” Father tried to conserve the results of the meeting and develop the people by having later on a social gathering at the church. 42

Work had begun to restore both spirit and community damaged by the yellow fever epidemic. Perhaps if anything good came from the fever, it was that the nation rallied to the aid of the stricken. The war that had divided the country was overlooked and all mustered resources to help fight one common enemy. Contributions flowed in from sister cities in the South, those west of the Mississippi, and from many northern cities that o several years before had sent arms and soldiers against the South. Contributions from New York alone totaled $56,804.16. The nation grieved with those who had lost so much to the fever and opened both their hearts and pocketbooks in an effort to aid in their recovery.43

Bibliography

-

- Dr. J. Millen Darnell, “A Brief Historical Survey of Germantown Tennessee.”

- Tennessee State Directory, Vol. 2, 1883-1974 (Nashville: Wheeler, Marshall & Brice,

Publishers, 1873), p. 185. - Bernice Taylor Cargill and Brenda Bethea Connelly, ed., Settlers of Shelby County,

Tennessee and Adjoining Counties. (Memphis: Descendants of Early Settlers of Shelby

County Tennessee, 1989), 83-84; Goodspeed, 1048. - “Cemetery is Being Reclaimed,” Memphis Press-Scimitar, 27 July 1967.

- Ibid.

- George Sisler, “The Time Memphis Died,” Commercial Appeal, 24 August 1958.

- “Ibid; “Cholera Epidemic is Hitting many Cities,” Daily Graphic, New York, N.Y., 25 June 1873

- Ibid.

- Ibid.

- Harry F. Cloyes Collection; Gerald M. Capers, Jr. The Biography of a River Town. (NewOrleans: Gerald M. Capers, Jr., 1966), 194.

- Gerald M. Capers, Jr. The Biography of a River Town (New Orleans: Gerald M. Capers, Jr., 1966), 194

- Ibid.

- Charles Thornton. “Yellow Fever’s Horror Recalled 100 Years After Its Departure,” Press Scimitar, 7 August 1978; J.M. Keating. A History of the Yellow Fever Epidemic 1978 (Memphis: The Howard Association, 1879), 105.

- Keating, 106-107; Capers, 194-195.

- Young, Standard History of Memphis, Tennessee, 173.

- Dr. Charles Crawford, “Epidemic, Bankruptcy took City to Bottom, The Appeal of Memphis, A Retrospective of 1 Decade, a special supplement to the Commercial Appeal, 21 April 1991, J19; Summers, 11-17; Capers, 191.

- Ibid.

- Sisler, “Bygone Days – 75 Years Ago – August 25, 1878,” Commercial Appeal, 24 August 1953

- Young, 171

- Ibid; Keating, 110; “Panic Marks Flight From Stricken City.” Commercial Appeal, 1 January 1940.

- “Bygone Days – 75 Years Ago – August 17, 1878,” Commercial Appeal, 17 August 1953; “75 Years Ago – August 21, 1878,” Commercial Appeal, 20 August 1953; Young 172; “Horrors of Plague Live on Thru Years,” Evening Appeal, 27 December 1932.

- “Bygone Days – 75 Years Ago – September 30, 1978,” Commercial Appeal, 30 September 1953.

- Magness. Good Abode, 146.

- Goodspeed, 1012

- Susan Taylor, “Welcome to Germantown,” Midsouth Magazine, a supplement to the Commercial Appeal, 24 February 1974, 304; “How It Began,” Germantown Express, 28 October 1971.

- Keating, 180.

- “Cemetery is Being Reclaimed,” Memphis Press-Scimitar.

- Ibid.

- Letter to Mrs. William H. Stovall from sister, Bettie, Memphis, October 8, 1878, from the private collection of D.E. Ashley.

- Letter to Mrs. William H. Stovall from sister, Bettie, Memphis, October 8, 1878, from the private collection of D.E. Ashley.

- Sisler.

- “The Camp Near Memphis – The Horrors of that City – A New Orleans Incident,” Ogle County Press, Polo Illinois, 21 September 1878.

- “Dread Epidemic’s End is Hailed by Appeal:” Commercial Appeal, 1 January 1940.

- “Did you Know,” Shelby Sun-Times , 10 September 1992; Keating, 239-240.

- Keating, 150.

- Keating, 150.

- Keating, 239-240

- “Dread Epidemic’s End is Hailed by Appeal;” Only doctors, Hearse Seen at Toll Gate,” Commercial Appeal, 1 January 1940.

- Keating, 193-194.

- Ibid.

- Plautus Iberus Lipsey memoir, Baptist Clergyman, author, editor, and son of Reverend John Washington Lipsey, (1865-1947) TSLA MSS. Accession Number 1888, Box 6 Tennessee State Archives, 29-30.

- Lipsey manuscript, 30.

- Keating, 337-359.