John Gray House

By Andrew Pouncey

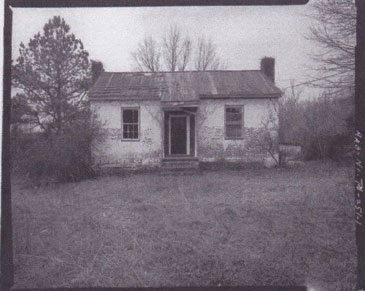

Alderman David Halle, liaison to the Germantown Historic Commission, was instrumental in negotiations for this 500 sq. ft., 150-year-old house being moved to the City of Germantown. The John Gray House stood in the rights-of-way of Highway 64 construction and had to be either moved or destroyed. The house, built around 1840, was purportedly the oldest brick structure in Shelby County made of brick fired on the site. Its relocation into Germantown places it in Municipal Park, with access off Watkins Lane, at Germantown Road South.

The late Mary Gray Swift’s Trust gave the house to the State at no cost. Swift, a housekeeper for the Halle family for nearly 50 years, owned the land on which the house stood. Before she died, she agreed to allow the house to be moved to Germantown. The structure went by many names – Carr House, Youngblood House, Historic Highway 64 House, and Germantown Historic House. The plan was to renovate the house and turn it into a museum which would double as the headquarters for the Germantown Historic Committee.1

The city received a contract/grant for $35,000 from the state on September 12, 1989, covering the moving cost to move the house to Germantown. Germantown allocated $40,000 to restore and preserve the house once it was relocated on its new foundation.

Prior to the relocation, the state appropriated $75,000 to a private archeological firm to conduct an archaeological dig at the current site of the house. The contract stated that all recovered artifacts would become the property of the state; however, the City was informed by the Department of Transportation, that these recovered items would be on permanent loan to the City of Germantown and placed in the historic home after its restoration.2

On Sept. 25, 1989, the Board of Mayor and Aldermen (BMA) hired Harland Bartholomew & Associates (HBA) for $6,700 to prepare working drawings for the preservation and restoration. John Hopkins was also engaged at that time as a Preservation/Restoration Consultant for a fee of $1,300. In June 1990, the BMA signed a contract for $42,368 with Design Specialties & Construction, In., for the exterior renovation work based on HBA’s plans. On Aug. 13, 1990, the Board voted to rehire HBA in the amount of $9,750 to oversee the work being done by the contractor as well as prepare specifications for interior restoration. The restoration had to meet Department of Interior specifications/guidelines and retain its 1840 character in order to utilize State funding. Tennessee’s funding was looked upon as a grant and the money Germantown was spending was viewed as matching funds.3

The house was east of Interstate 40 but plans to widen U.S. 64 meant the structure had to be moved. The State Department of Transportation agreed to move the house to the Germantown Municipal Park site between the pavilion and the new Civic Center. The State also required that if the house moved to Germantown, it could not stand with any other historic structure. That is how Municipal Park was chosen as its permanent home.

The move, which took the house down Rockcreek Parkway through Countrywood and along Germantown Parkway took about seven hours. The restoration was begun in December 1989, eight months after it was placed at the site in August of 1990.4

The John Gray House is historically significant as a western Tennessee cultural resource for the insights it sheds on the region’s pre-Civil War architectural history and rural life among middle-class farm folk. An architectural form, unusual in the region, the structure represents an important link in the demographic spread of this vernacular form in conjunction with the westward expansion of the American frontier. The dwelling also provides a rare example of a middle-class residential structure from the period. No more than a dozen antebellum brick residences survive in Shelby County. Of these, the John Gray House is the only known single-story example. The structure’s period of significance has been designated from 1835-1881, years that represent the span of time between the house’s earliest potential construction date and the date of a two-room frame addition (dismantled ca. 1961) to what is now the south end room, or parlor.

Its new orientation, relocation setting, and general environment are comparable to those of the historic location and are compatible with the structure’s historical significance. The Germantown Historic Committee, in conjunction with the City of Germantown and Germantown Parks and Recreational Department, partially furnished the rooms to reflect farmstead activities and usage typical of the period of significance and the lifestyles of the structure’s historical occupants from the mid-1800s through the early 1880s.

According to historical documentation, the property was acquired as a land grant by John C. McLemore in 1824 and subsequently sold to Thomas Youngblood, a farmer in 1832. The property, amounting to 207 acres, was later purchased by John Gray in 1844. Although the house foundation may have been laid toward the end of the Youngblood tenure, it is probable that the residence was erected following the Gray purchase and prior to 1851. John Gray’s tenancy lasted from 1844 to 1851. According to the 1850 Federal Census for Shelby County, the dwelling’s first documents occupants – the John E. Gray household – consisted of a widowed father and three individuals who were presumably his children: a young female adult and two teenaged boys. Gray was a farmer whose main crop was Indian corn. His total worth, excluding slave holdings, was listed as amounting to only $2,000.00 in 1850. The 1850 Slave Schedule shows Gray as owning sixteen slaves, ranging in age from six months to thirty-five years. John Gray became a major figure in the development of the Morning Sun community in the years prior to the Civil war, and the area’s oral traditions have linked him with the house’s construction for many years. Dr. William H. Chambers’ proprietorship of the property lasted from 1852 to 1865. Documentary evidence is inconclusive as to whether he actually lived on the property at any time during his ownership. The next occupants of the property came into its ownership by the failure of Dr. Chambers, who had mortgaged the farmstead to Mrs. Sarah Chapman Law (referred to as the “Mother of the Confederacy” and organizer of the Southern Mothers to aid southern troops) to cover his indebtedness to her. By agreement, Sarah C. Law’s son-in-law and daughter, Dr. William Bibb Wright and Sarah R. M. (Law) Wright, were allowed to live on the property for the remainder of the Civil War. The property was sold in 1865 to satisfy the mortgage to Mrs. Law, and the settlement effectively transferred the property to Sarah R. M. (Law) Wright. The property was sold in December 1865, to Jeremiah B. Steward, whose tenureship lasted until 1870. By 1868, however, the Steward family may have lived elsewhere. It appears that Dr. A.W. Caldwell, another physician farmer, occupied the tract with his family under some form of the unrecorded land contract. Dr. Caldwell and his wife, Mary A. Caldwell, owned the property from 1870-1873 and then sold it to Isham M. Davis, who owned the farmstead until 1908. In that year J.G. Simerson acquired the property, and following his death in 1921, Mattie Cooper Simerson, his widow, continued to live on the property and raised a family of six children to maturity. In 1955 the property was sold to Richard Barber, who occupied the brick house until 1961, when Mary F. and Roxie Swift purchased twenty-five acres of the property, including the house. Mary F. Swift was believed to be descended from former Gray family slaves. The Swifts did not occupy the house but rented it to several tenants over the time of their ownership. According to information provided by the Simerson family, who were neighbors, the brick house was last occupied in ca. 1980, and the property’s deterioration began to occur soon thereafter. In 1985 Mary F. Swift filed a quitclaim conveyance of the now twenty-acre parcel to David P. Halle, Jr. and Frank O. Oakes, Jr. in fee simple. Mrs. Swift had been a housekeeper in the Halle family for decades prior to her failing health and subsequent death in 1989.

Morning Sun, an unincorporated farming settlement, developed in the 1840s. It was here, along on a post, or stage road known as the Memphis-Somerville Road, a route that closely paralleled present-day State Route 15 (U.S. 64) and provided a much-utilized transportation artery during westward expansion, that the John Gray House was constructed. This became the first chartered road in Shelby County in 1846.

The modest, two-room floor plan is folk or vernacular architectural configuration known as a hall and parlor plan. Although this design was uncommon in western Tennessee, having appeared during the 1740s in the Tidewater region of Maryland and Virginia, incoming settlers from these areas established homesteads in easter and middle Tennessee during the last quarter of the eighteenth century that were consistent with the hall and parlor plan-type.

There appears to have been little architectural adaptation of the house plan to fit the southern climate, particularly during summer months, when a 3–4-foot space of hot air existed above doors and windows, rendering the house uncomfortable during extended periods of heat. Construction of a residence built entirely of brick appears to run contrary to the norms of antebellum structures in Shelby County and western Tennessee as a whole. Its construction in brick did indicate a greater expenditure than a simple log or frame construction.

The larger hall was used for mealtimes and informal, daily activities, while the smaller parlor had nicer furniture and also served as the bedchamber. The attic loft served both as storage space and sleeping quarters for young males in the family. Construction techniques of interest for their insights into rural western Tennessee masonry and carpentry techniques during this period include the house’s hand-made brick, “sleeper” or log floor joists, and log poles used in the fashioning of roof rafters. These elements, crude in execution, exist alongside such careful finishing details as dual-room chair railing and a penciling technique used in outlining mortar joints on exterior brick surfaces.

The structure is significant for its age, construction, and decorative techniques, regional uniqueness as a building style in western Tennessee, and as one of the oldest surviving brick masonry residences in Shelby County, whose middle-class inhabitants typified much of the period’s local settlers.

The structure retains its significance, as well as its communicative and information potential because:

- It represents modest housing built by middle-class, western Tennessee settlers in the mid-nineteenth century.

- It is an artifact of nineteenth-century technology and material culture and provides insight into social, cultural, and demographic factors relating to hall and parlor houses in Tennessee, as well as an important link in the demographic spread of this vernacular form in conjunction with the westward expansion of the American frontier.

- It provides the opportunity for ongoing investigation of brick masonry technology in western Tennessee during this era.

- It retains, through its architectural integrity and a relatively small amount of structural alteration, the potential for yielding significant information concerning the interpretation and preservation of the region’s cultural resources.

- It is an important link in our understanding of the architectural history and rural life of western Tennessee.

- It represents a rare example of a standing-middle class structure from the period and provides the opportunity to examine architectural trends, design forms, and material culture available to and desirable by members of this class.

- Its brick construction may provide the opportunity to review common assumptions regarding the expense of its construction, thereby opening questions relative to the prevalence of frame construction as a preferred material in the area.

- The period from 1835-1881 allows for the investigation of a range of thematic and regional topics – antebellum, Civil War era, and postbellum – in order to document regional continuity and change through time.

Source:

- The Germantown News, Thursday, August 23, 1990

- The Germantown News, Thursday, September 28, 1989, p. 18.

- Ibid, August 23, 1990

- The Commercial Appeal, Memphis, Thursday, December 14, 1989

- Gray, John, House, Shelby Co., TN, National Register of Historic Place Continuation Sheet, Statement of Significance, Sec. Number 8, Page 1-6

The U.S. Department of the Interior, National Park Service, did not approve the City of Germantown’s application to receive a place on The National Register of Historic Places.

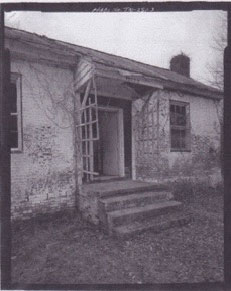

House on Rights-of-Way on Highway 64

Front Facade

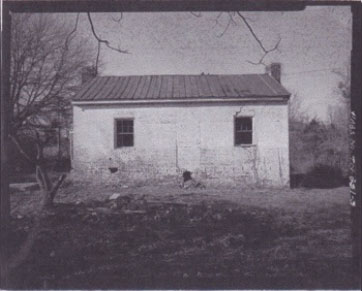

Rear Facade

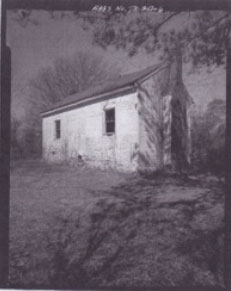

Relocating John Gray House

August 1990 (Municipal Park)

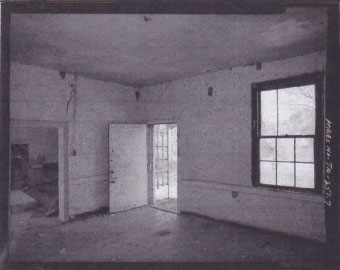

Smaller Parlor

Larger Hall

Larger Hall (looking away from door)

John Gray House Today (2021), in Municipal Park

West Tennessee Historical Marker

Front Facade

Rear Facade

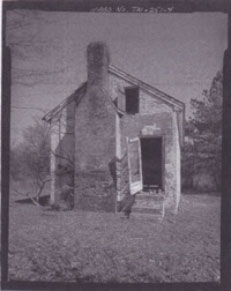

South Chimney